Rebuilding Skopje, 2022

Rebuilding Skopje, in: Modulor, 3/2022

Villa Auska in Palanga, 2022

Villa Auska in Palanga, Litauen, Architekt Juozas Šipalis, in: Modulor, 3/2022

Sputnik-Observatorium in Szombathely, 2022

Sputnik-Observatorium in Szombathely, H, von Elemér Zalotay, in: Modulor, 1/2022

Új építészeti magánmúzeum nyílik Jerevánban, 2020

Új építészeti magánmúzeum nyílik Jerevánban, epiteszforum.hu, 2020

Egy terv, egy történet, szentendrei nyaraló svájci építésztől, 2020

Skopje - utopické město v béton brut, 2017

Artikel zu Architektur und Stadtentwicklung in Skopje, in: ERA21, Nr. 3, 2017

Ein Wochenende in Tbilisi, 2016

Artikel zu Architektur und Innenarchitektur in Tiflis, in: AIT, Nr. 4, 2016

Skopje - Utopie in Béton brut, 2016

Artikel zu Architektur und Stadtentwicklung in Skopje, in: Phoenix - Bauen im Bestand, Nr. 6, 2016

Architekturreise nach Georgien, 2016

Auf dem Weg in den Grossen Kaukasus: Denkmal der georgisch-russischen Freundschaft, Architektur: G. Chakhava

Georgien ist beinahe doppelt so gross wie die Schweiz, hat aber nur halb so viele Einwohner. Eindrückliche Naturlandschaften vom Schwarzen Meer bis zum Kaukasus und Bauten aus der Sowjetzeit machen das Land zu einer interessanten Destination.....

Ganzer Artikel zur Architektur in Georgien auf swiss-architects.com

A10- Out of Obscurity, 2015

Church at Ildikó tér, XI. Budapest by István Szabó, 1981, Article by Emiel Lamers, photo Peter Sägesser, ostarchitektur.com, more photos here

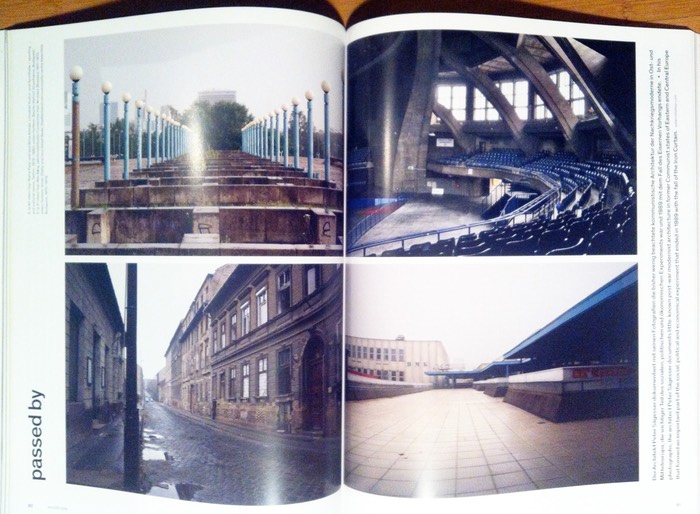

Unorte - Non Places, Form, 2015

Exhibition "Neglected architecture", 2014

Neglected Architecture, Nachkriegsmoderne in Ost- und Mitteleuropa

Ausstellung in Frankfurt am Main

Neglected Grassland

Neue Kräme 29 (Sandhofpassage)

60311 Frankfurt am Main

Vernissage:

Donnerstag, 6. November 2014, ab 19 Uhr

DJ-Sets:

Hans Romanov und Oliverse

Ausstellungsdauer: 7.11. – 7.12.2014

Budapest Concrete, 2014

Budapest Concrete, in: Stylepark, May 2014

Budapest’s fourth metro line opened this spring. Hopes of additional urban development projects are associated with this infrastructure project. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Hungarian architecture has been shaped by a search for a national identity, on the one hand, and a wish to achieve international status, on the other. In Budapest you can view ornamental buildings by Ödön Lechner alongside Bauhaus architecture, organic architecture side by side with post-War Modernism. Since the Wall came down in 1989, construction activity has focused on commercial architecture and new architectural highlights are rare. It is perhaps symptomatic of Hungary’s current political situation that the best example of contemporary Hungarian architecture is to be found beneath the ground, in the new M4 subway line.

As early as 1896, the first subway line went into operation in Budapest. It was the first ever subway on the European continent. Today, the three underground lines serve 3.5 million passengers daily. In the 1980s, planning commenced on a fourth line, but it was not until 2004 that construction of the M4 started. This April the 7.34-kilometer-long line was commissioned. It connects the Eastern Railway Station downtown with the large housing estates and the Kelenföld Station in the city’s southwest. And it is doubtless Budapest’s most important infrastructure project in 30 years. The ten stops were designed by different architectural offices, the two most beautiful ones, namely F!vám tér and Szent Gellért tér, were designed by the young company sporaarchitects.

The architects encountered various obstacles when designing the stops. The 1980s planning had to be adapted to current requirements. The stops are, moreover, located in an area that is part of the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site so that intervention at the surface had to be kept to a minimum. Above all, planning the transport node at F!vám tér was a tall task. There, the new subway interconnects with existing bus, tram and shipping lines, all of which had to be linked up. The same construction system was thus used for both stops. Slits were cut into the ground from above, and the earth in-between excavated storey by storey downwards to track-level. At the same time, the walls were reinforced by an inset box structure and massive struts. The concrete box and the reinforcing struts absorb the huge forces involved, as both stops are in the direct vicinity of the Danube. The architectural and structural idea derives from a change in the distribution of the bracing struts. This enabled a flexible response to the frequent changes in the planning process without the concept as a whole needing to be changed.

For the proposal, the architects first took their cue from the structure of a human bone. The matrix of struts also symbolizes the different levels of the transport system and the intersecting passenger routes. Ádám Hatvani, a partner at sporaarchitects, qualifies this by saying: “The space that arises is not just functional, but also has a mystic mood. Not that this atmosphere was the objective from the outset, as it is more the result of a process. We designed the structurally necessary steps and used the potential they afforded for a public space underground. The result is an architectural response to a specific, structural problem.” You get a sense of the sheer space best if you stand right at the bottom on the platform. Although you are now 30 meters below ground, you never have the feeling that you are confined or shut in.

The struts bring natural light from above right down to the platform level. Passengers will be reminded of the light atmosphere in Budapest’s West Railway Stations, designed in 1874 by none other than Gustave Eiffel. The material shape given both subway stations is similar: fairfaced concrete and Corten steel panels dominate the walls. In the Szent Gellért tér stop, the tunnels are tunnels are clad with colored mosaic stones. Chairs by Konstantin Grcic reiterated the motif of the reinforcing concrete grid. The absence of adverts is striking. While other stops on the Budapest subway boast walls covered with ads along the escalators, there are none here. After protracted negotiations with the developer, the architects managed to make certain that only at a few places were large LED screens installed. They will be used to display ads and art videos. A full 140 years after Gustave Eiffel’s West Railway Station, sporaarchitects demonstrate with the two new subway stops that infrastructure buildings offer great design potential. The new line will influence other urban development projects for sure. Hopefully as regards architectural quality, too.

www.sporaarchitects.hu

Best of Budapest, 2013

Best of Budapest, in: Frame Magazine, 2013

Tordre le cou aux clichés sur l'Est, 2013

Tordre le cou aux clichés sur l'Est, in: La Liberté, 2013

Kenzo Tange and Socialism, 2013

Kenzo Tange and Socialism, in: Stylepark, February 2013

In the wake of the devastating earthquake of 1963, which almost completely destroyed Skopje, the now capital of Macedonia, Kenzo Tange devised a master plan for a new city that did in fact become a reality, as fragmentary as its formation may have been. But the vestiges of Yugoslavian Socialism made possible by its authoritarian constructs are now under threat from modern-day plans.

A whole 20 seconds: That was the duration of the earthquake that destroyed the city of Skopje almost 50 years ago on July 26, 1963. More than 1,000 lost their lives and three quarters of the city was reduced to rubble. The Ottoman old town north of the Vardar River was the only part to emerge from the quake mostly unscathed. Barely had the last aftershocks subsided and authorities were already set on the city’s reconstruction. Skopje would become an experimental laboratory for a 1970s utopian socialist vision of urban

development.

Skopje’s fate became the subject of worldwide interest, receiving offers of support and aid from across the globe. Neither a part of the Eastern bloc nor a member of NATO, Yugoslavia had been pursuing its own political path during the Cold War. As a result Skopje provided the backdrop for the first meeting between US and Soviet soldiers since World War II deployed to assist with the city’s reconstruction. Understandably the undertaking assumed huge symbolic importance for the United Nations who two years after the earthquake announced an urban planning competition for the city in a bid to demonstrate that solidarity was in fact possible under their guidance. Eight architectural firms were invited to take part. Four from Yugoslavia, four from other countries. The list of those invited boasted the leading urban planners of the time: Bakema and Van den Broek from Holland, Kenzo Tange from Japan and Aleksandar Đorđević, Radovan Miščević, Fedor Wenzler and Edvard Ravnikar from Yugoslavia. Projects by Miščević/Wenzler and Kenzo Tange came out on top with first prize. The fact that Kenzo Tange’s project was ultimately chosen for implementation was closely related to the radical vision and the greater propagandistic potential it brought with it, for the United Nations as much as for Yugoslavia and Japan.

In the same year, Kenzo Tange made a guest appearance at the CIAM X Congress in Dubrovnik. Impressed by the city’s lucid urban layout, Dubrovnik became the paragon for Skopje’s redevelopment. As in Dubrovnik, plans foresaw a “city wall” formed of residential buildings encircling the city, while a monumental central access route would symbolize a “city gate” – a linear axis conceived as a multi-level link between the train station and city center and flanked by office high-rises and malls.

Tange was one of key members of the Japanese “Metabolists”. Having proposed an urban macrostructure for Tokyo as early as 1960, he now had the chance to realize his ideas in Skopje; though it must be said that Tange did see an advantage in the fact that Yugoslavia was a Socialist country. “Yugoslavia is a socialist country in which land is not privately held, the city government had sufficient power to make it possible to introduce our total plan.” (Lin Zhongjie: Kenzo Tange and the Metabolist Movement, Urban Utopias of Modern Japan, New York, 2010)

This top-down approach may have been in touch with the zeitgeist but not with the reality on the ground. While they had their heads down working on the master plan, the city had moved on in its development. In the end only a part of Tange’s plan was realized. Today, the “city wall” is around a third of the size originally planned, whereas the train station and the the ground. While they had their heads down working on the master plan, the city had moved on in its development. In the end only a part of Tange’s plan was realized. Today, the “city wall” is around a third of the size originally planned, whereas the train station and the commercial bank tower were the only elements of the “city gate” to become a reality. The 1973 City Shopping Center provides a mere inkling of how this “city gate” axis might look today.

Although Tange’s master plan was only realized in rather fragmentary fashion, it certainly paved the way for other visionary projects, such as the Goce Delčev Student Complex and the Georgi Konstantinovski City Archive. Macedonian architect Janko Konstantinov also created an organic concrete sculpture as the Central Skopje Post Office, while fellow native Marko Musić concentrated on the old town’s labyrinth of little lanes and squares in his design for the university building. But the most impressive of all is the Macedonian Opera and Ballet built in 1979. It looks less like a building, more like a mountain range whose slopes cascade down to the Vardar River, reminiscent of the Oslo Opera House by Snøhetta or modern-day buildings by Zaha Hadid.

Today the government shows little sympathy towards these ailing architectural relics from the 1960s and 1970s. The buildings are barely even maintained. Some of the rooms on the Goce Delčev complex have been declared inhabitable by dint of water leaks and across the city large-scale demolition greets you whichever way you turn. The governing Conservatives are now planning to erect a plethora of monuments, buildings and memorials as part of their “Skopje 2014” initiative – a task seen as formative for this small country’s identity. The architects on board have been instructed to stick to a pseudo-classical style in their designs. Whereby the aim of “Skopje 2014” manifests itself as nothing less than a rewriting of history; the buildings that bear witness to the period of Socialism are a naturally rather troublesome for such an undertaking. Since the new builds will primarily house government ministries, they will not yield any kind of return and will certainly prove a burden for the state in the future. I guess that the funds so desperately needed for the maintenance of such wonderful buildings as the Opera or the student complex will remain consistent in their absence.

Sarajevo in Schlieren, 2013

Sarajevo in Schlieren, Hochparterre, Jan. 2013

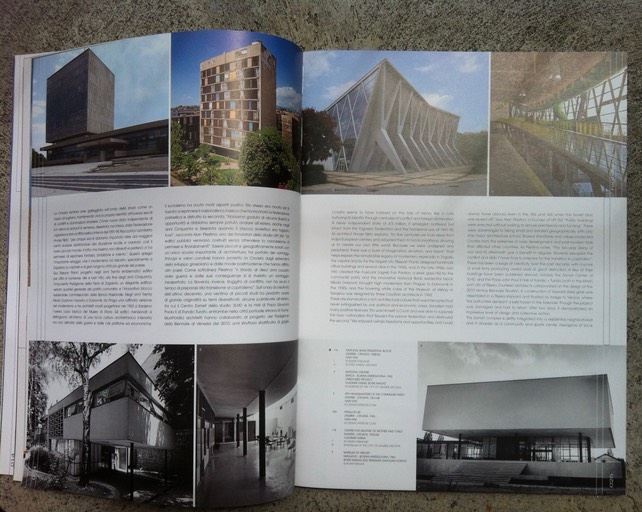

Architektur in Kroatien, 2011

Architektur in Kroatien, in: The Plan, Dez. 11 / Jan. 12

The model housing development in Òbuda, 2010

The model housing development in Òbuda, in: Stylepark, December 2010

In the district of Òbuda in Budapest various examples of socialist residential buildings stand alongside one another. On the one hand you find buildings in the style of Socialist Realism, on the other there are huge pre-fabricated buildings dating from the 1970s. Between, hidden behind trees, is a small group of houses which were erected around 1960 as a model housing development.

The model project came about as a result of a speech by Nikita Khrushchev. In 1954, the Russian head of government assembled the leading architects and building functionaries in the Soviet Union for an "All-Union Conference of the Construction Industry". He used the occasion to publicly declare the de-Stalinization of building culture and the elimination of "conservatism in architecture" - a message which set a trend throughout the entire Eastern Bloc. Khrushchev opposed Socialist Realism and propagated the industrial production of architecture, still, it goes without saying, in the socialist sense.

In so doing, Khrushchev was responding to the grave deficits afflicting large parts of the population in the entire post-War Eastern Bloc. As in other market segments, there was a high demand for residential construction which at the time manual building methods were unable to satisfy. In order to reduce the cost of housing construction and increase productivity, efforts had been channeled for far too long into reducing the size of and fittings in apartments rather than improving the technical possibilities. The result was small, one-room apartments for families with several children. Furthermore, the only furniture available on the market was relatively large and barely fitted in the small dwellings.

Given this unsatisfactory situation, in 1957 the Hungarian Ministry of Residential Construction initiated "Plan C", which had various aims: To make up the ten-year deficit in residential construction within two years, for which productivity in the building industry needed to be increased. In addition more spacious, higher quality apartments were to be built, and, not least of all, furniture was to be made available that reflected the needs of the residents, was broader in range, and of better quality.

In 1958 the Ministry of Residential Construction organized an architectural competition for experimental housing - innovative footprints being the order of the day. Cutting-edge materials and building technology, such as concrete produced on the building site itself, pre-fabricated wall segments, and a light construction style that saved raw materials were to be used for those designs that would emerge as winners. The prototypes, which would be tested in model settlements, would then be built throughout the country. Some 180 projects were submitted. Various architects subsequently built residential buildings, small shops, a school and a kindergarten.

The average size of apartments in the Òbuda model residential settlement was 48 square meters. The smallest, originally intended for couples with one child, measured between 36 and 41 square meters. The largest - for up to six people - were between 68 and 76 square meters in size. What is also striking is that the color design of the buildings highlights their constructive principles. There was also a furniture design competition. Here too, in addition to a new, contemporary formal language, the brief was for solutions for cheap, rational production methods. The results of both competitions were initially published in competition catalogues and then in the press - with the intention of winning people over to the new architecture.

Unfortunately things never got past the experiment stage. Only isolated ideas from the Òbuda development were used for other building projects. That was not the case with the new furniture. Not only did it appear quickly in many Hungarian households, it also formed the basis for the creation of a modern furniture industry in Hungary.

Maghàz, Budapest, 2010

Maghàz Budapest, in: Wohnstadt Bern, 2010

Ostarchitektur, 2008

Ostarchitektur, in: Stylepark 4, 2008